Just as it seems one front is closed, a twist restarts hostilities – the latest involving a capricious US president and an insecure Turkish one, with the Kurds in northern Syria bearing the brunt. An abrupt American withdrawal paved the way for yet another conflagration, yet another power calculus – as Bashar Assad extends support to the Kurds – and yet another lease of life for ISIS. More than 100,000 people are on the move in northern Syria. And at least 750 people with suspected links to ISIS have reportedly broken out of a camp in north-east Syria, raising the possibility of a new shot in the arm for the terror group.

When, earlier this year, the Sudanese revolution began to gather steam, the Syria bogeyman was predictably summoned. It didn’t help that Sudan had received Syrian refugees. Their increasing number in Sudan – a country more accustomed to sending refugees than receiving them – was its own live warning. Is this what you want? The Syrian scenario was presented as an inevitability: this is what happens when people demand the overthrow of their leaders, when the natural order is challenged. Things certainly will fall apart.

The supposed Syria menace is backed by a cast of similar characters in the region. Libya, riven by factional fighting and only last month the scene of US airstrikes against militants, is also often mentioned with a shudder, a “there but for the grace of God go we” if we continue challenging the status quo. Then there is Egypt, a country that, in its regression after the Arab spring, is now such a closely patrolled security state that the number of political prisoners in its jails is literally inestimable.

Each day seems to bring a fresh hell across these three countries, a rebuke to all those who think that in the Arab world there is another way of politics that doesn’t involve strongmen. You hear this logic internalised and vocalised by Arabs themselves in a sort of exceptionalist self-flattery. It’s just our temperament, you see, we need leaders to manage our strong and stubborn character.

It doesn’t seem to be working. This is the year that the spirit of protest in the region was proven to only have been dormant, rather than extinct. The Sudanese overthrew Omar al-Bashir in a grand majestic revolution, where a revolutionary body of thousands pitted itself against the formidable machinery of the state’s military dictatorship. Despite the country already suffering from ethnic and tribal divides so pronounced that an entire murderous paramilitary complex arose from its fissures, despite there being a history of bloody conflict that pointed more towards a Syria- or Libya-style disintegration, this was not enough to chill the need for change. Even after hundreds were slaughtered and the internet shut down, protesters still coordinated and found their way on to the streets of Sudanese cities.

Not even in Egypt has the protest movement died. If there is any indication that scorched earth suppression is inevitably a short-term solution, it is that protests are happening again. In September the first significant protests since former army chief Abdel Fatah al-Sisi came to power. In this country a tweet or a Facebook post can result in a jail sentence; and the security stakes are so high that a protester will leave home expecting not to return. Many did not. Estimates are that about 2,000 were detained.

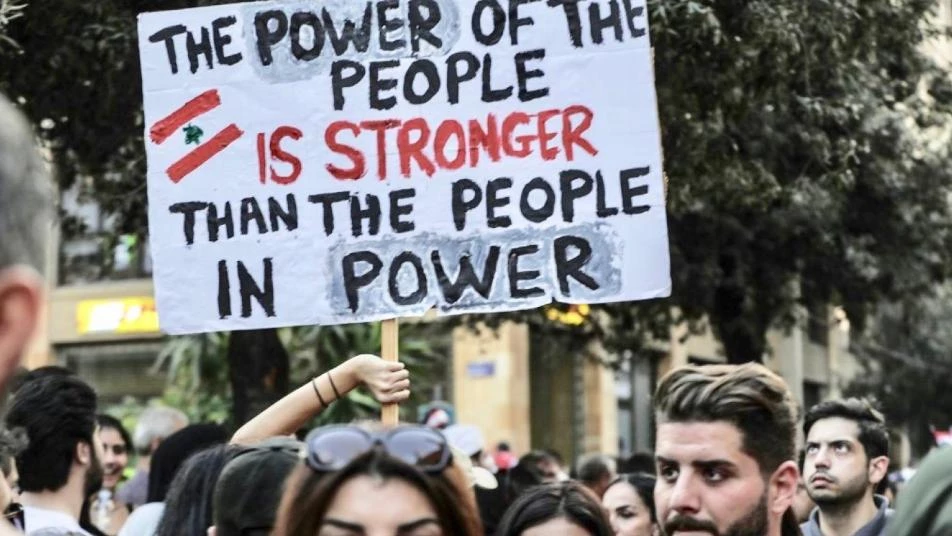

Last week it was Lebanon, where protests have erupted across several cities. There is now a similar kaleidoscope of images that plays out across Arab cities where lines have been drawn between the people and the government. Sometimes one has to squint to work out whether the throng of bodies and mobile phone screen constellations is in Beirut, Cairo or Khartoum. Both in Lebanon and in Sudan, one scene repeated itself with uncanny similarity; protesters addressing the security forces, the army and the police, rebuking them for not crossing the lines to join their comrades. In Sudan many did cross those lines, joining the revolutionaries against their own employers.

That defection, or demand for defection, lies at the heart of the resurgence of political protest. If the Arab revolutions that grew eight years ago were about removing lone dictators, the current wave is about removing an establishment that for too long has drained resources. Egypt’s protests were triggered by a former government contractor who exposed Sisi’s epic profligacy. In Sudan, food prices and a scarcity of basics pushed the middle class over the edge while those in power luxuriated in their spoils. In Lebanon, a tax on WhatsApp voice calls tipped those fed up with economic mismanagement over the edge. Last month it emerged that the prime minister, Saad Hariri, had gifted $16m of his own money to a South African model six years ago.

Dissent will not be chilled by pointing to the failures of the Arab spring. Warnings to remain quiet, pointing to the pitfalls of taking action, are increasingly going unheeded. Arabs are beginning to realise that to excessively fear what may happen in the future is to be tricked into submitting to an unacceptable present.

By Nesrine Malik

Edited according to Orient Net

Link to the original source of the Guardian

التعليقات (0)