On a busy high street in northern Jordan, shoppers bustle past the stalls selling toys, shoes, bikes and kettles.

In a kitchen nearby, a baker bakes the next day’s bread.

Across town, a couple prepare for their wedding, while a young boy prepares to return to school.

My favourite thing about Refugee Camp: Our Desert Home (BBC2) is that it portrays the residents of Zaatari, Jordan’s fourth-biggest city, as just normal people.

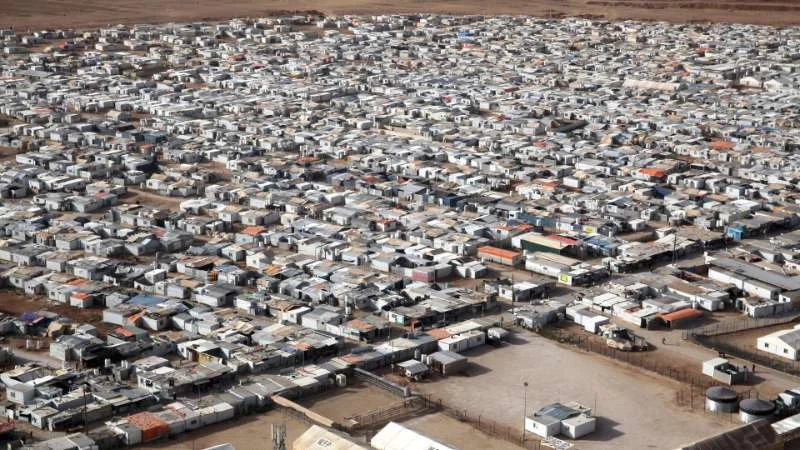

But the title gives the game away. Zaatari isn’t a normal town. It’s the world’s biggest Syrian refugee camp. And just four years ago, none of its 80,000 residents lived there.

If you haven’t heard of Zaatari, you might have seen it in photos. It’s often used to show the scale of the Syrian refugee crisis (which has created more than five million refugees, and counting), usually broadcast as an aerial photo of the camp. Endless rows of prefab containers stretch into the desert – reminding us just how insulated Europe has been from the reality of the crisis.

Refugee Camp takes us down to ground level. We meet Ziad, a grandfather who, despite living in the desert, has managed to cultivate a small herb garden outside his back door. Today, he’s planting a lemon tree.

In one of Zaatari’s 11 hospitals, we come across Muhammad, a boy with a badly damaged leg who is waiting for the go-ahead to return to school.

Across town, we watch Moussa’s last shave before his wedding – and then follow Mataba, his fiancee, as she picks a bridal gown.

Zaatari has more than 3,000 businesses, one of which sells wedding dresses – much to the surprise of Anita Rani, the most engaging of the show’s three presenters.

“This isn’t what I was expecting at all,” Rani says. “This is my first time in a refugee camp, so maybe this isn’t a typical setup.”

She’s right, actually. Half an hour away, there’s another camp, Azraq, where the Jordanian government rarely allow journalists, let alone a BBC documentary team. Conditions at Azraq are far more depressing, according to aid workers who deliver services there.

Similarly, we’re not shown the desperate scenes just a few miles to the north, at the border with Syria. There, the Jordanian government has left more than 60,000 would-be refugees stranded in a makeshift camp in no-man’s land.

Finally, we never see what life is like outside the camps, in the towns and cities, where the majority of Syrian refugees live. Only a fifth of them have homes in camps such as Zaatari. The rest have to pay rent, despite the fact that most of them are not allowed to work.

But none of this should take away from the achievements of this moving documentary, which has given human faces to a camp we usually only see from the air.

Nor does it shy from the small tragedies that take place at Zaatari every day. Moussa and Mataba provide the episode with an uplifting through-narrative – but even their story is tinged with sadness. Mataba blushes when she talks about Moussa. But the 18-year-old admits that if she was still in a peaceful Syria, she wouldn’t be getting married. She would be in the first year of a medical degree.

Then there’s Hafez, a jolly 15-year-old we meet in a bike shop. He walks to school with his brother, and we smile at their touching relationship. But then his brother goes inside, and Hafez walks back to the shop to work: he’s one of hundreds of thousands of Syrian children across the region who have dropped out of school to help their families make ends meet.

Young Muhammad’s narrative is similarly bitter-sweet. At the end of the show, he goes back to class – but he only left in the first place because his leg was badly hurt in an air strike. One bone is still loose, and there’s a hole in his knee. His mother died in the same bomb attack.

It is this kind of story that reminds Javid Abdelmoneim, one of Rani’s two co-presenters, of Zaatari’s central contradiction. “When you’re out and about in the camp itself, life is calm,” he says. “It feels safe, and people are getting on with things. It’s easy to forget that there’s a war going on just a few miles away. But here in the hospital, you meet people who have lost limbs, and really been affected by that violence. They’re victims of war, and it brings it home.”

التعليقات (0)