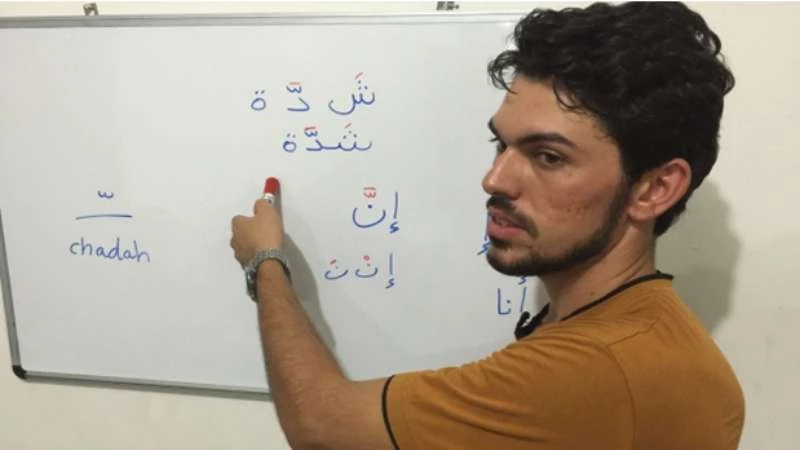

Arabic is a difficult language so the progress is slow, but it is steady.

In reality, Bakkour teaches the young Brazilians more than just his native tongue, for his students are also fascinated by the culture of his homeland.

Their questions range from wanting to know if he can marry four wives to asking if Syrians really cut off the hands of thieves Bakkour told Kim Brunhuber of the BBC with a smile.

Bakkour began teaching the Arabic night courses as a way of giving back to the country that so graciously offered to take him in after he decided to leave his difficult life in Syria behind and start over some place safer.

He says that after the peaceful revolution in Syria morphed into a brutal campaign of death and destruction by the Assad regime he lost many friends and came close to being killed himself.

But when it came time to leave, the list of options of where to go was a short one. When Brazil offered him refuge he took the South American country up on its offer and within a month of arriving he was given a Brazilian work permit and free Portuguese lessons.

Bakkour’s Arabic language students love hearing him tell stories about what life was like back in his homeland.

Many Brazilians also know little to nothing about what has been happening in Syria for the past five and a half years and they are eager to know why someone would leave the familiarity of their homeland and move halfway around the world to a foreign country.

They are also curious about his perceptions of Brazil and Rio, and about how he is handling adapting to life in a South American country and a major Brazilian city like Rio de Janeiro.

But recently the situation in Brazil has begun closing the doors on the hopes of other Syrians wishing to resettle in the country as well.

Former president Dilma Rousseff is facing impeachment proceedings because of corruption scandals and the interim president Michel Temer does not share Roussef’s "open-arms" policy regarding Syrian refugees.

While one former minister said that the goal of Roussef’s government was to accommodate 100,000 Syrians in five years, Temer is abandoning plans to bring in more refugees in a concerted effort to establish a law-and-order administration that will have national security as its top priority.

Recent terrorist attacks in Europe have also ignited the same fear among Brazilians that terrorists may sneak in amongst the refugees that has already spread to so many other parts of the world.

"It brought a negative view towards the Syrians," Alex Cuelho, a priest who runs a shelter at Sao Joao Batista Church, told Brunhuber. "Now there’s prejudice and fear of receiving Syrian refugees."

The Sao Joao Batista shelter in the Botafogo neighborhood of Rio de Janeiro is currently home to about 30 of the 2,200 Syrians who have been resettled in the country which has a population of 200 million. Only Canada and the U.S. have accepted more Syrian refugees than Brazil from the countries that make up the Americas.

If the current anti-refugee trend continues, Syrians already living in Brazil will not see their hopes of being reunited with other family members and friends whom they have encouraged to join them realized.

The negative attitudes and emotions have also begun to affect Syrians who are already living and working in Brazil such as Ahmad Hamada.

He says that shortly after he began selling Middle Eastern foods like falafel and kibe from a rolling cart on a busy street in downtown Rio, the police began to harass him.

"The police come, every day they say, ’You cannot sell here, you cannot sell here,’" Hamada told Brunhuber while standing next to his stand in front of a movie theater.

Fortunately for Hamada, one of his most influential customers happened to be Eduardo Paes, mayor of the city of Rio de Janeiro, who intervened on his behalf putting an end to the harassment and allowing him to stay.

"He is like my mother because he sees me, what happens,

Hamada asks just one thing of those suspicious and fearful Brazilians; “Please just get to know us.”

التعليقات (0)