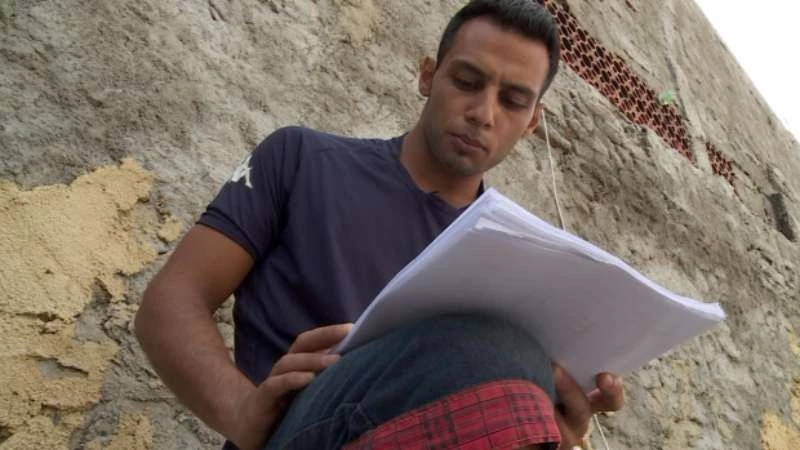

"How did I get here? Ya!" he laughs. "It was a little bit … complicated."

When Syria’s war tore apart his city of Aleppo three years ago, he says, his brother was arrested and tortured.

"Fifteen days, horrifying, torturing, abusing, and he did not see the sunlight," Abjada says.

He says he faced a terrible choice: the Assad regime demanded him to join its “army” to fight the rebels.

So I choose not to kill anybody and I leave the country," he tells CBC.

But where to go? Most of his friends ended up in European or Middle Eastern refugee camps — safe, but essentially imprisoned.

"Canada and Brazil, they are the only two countries they are giving Syrians a safe way to make a new life," Abjada says.

Abjada is one of more than 2,200 Syrians who have settled in this country of 200 million. Brazil has accepted the third-most Syrians in the Americas behind Canada and the U.S.

He arrived this year via Turkey, and has been staying at Sao Joao Batista, a small church in the Botafogo neighbourhood of Rio de Janeiro. The church has become a way station for close to 30 refugees.

As Abjada recounts his story, another Syrian refugee arrives from abroad. He says his name is Ali, and Abjada offers to help him settle in.

However, a shift in the country’s politics means Ali could be one of the last Syrians to arrive in Brazil.

Under former president Dilma Rousseff, the country had an "open-arms" policy. One former minister said his government’s goal was to accommodate 100,000 Syrians in five years. But now Rousseff faces impeachment proceedings because of corruption scandals.

Michel Temer, the interim president, has advertised a law-and-order administration with security as a top priority, and he is abandoning efforts to bring in more refugees.

Alex Cuelho, the priest who runs the shelter at Sao Joao Batista, says with increased visitors for the Olympics and recent attacks in Europe, "it brought a negative view towards the Syrians."

"Now there’s prejudice and fear of receiving Syrian refugees," Cuelho says.

Those negative attitudes and emotions have already touched Ahmad Hamada.

Soon after he set up a rolling cart on a busy street in downtown Rio selling Middle Eastern foods like falafel and kibe, he received visits from the police, who seemed to be targeting his stand.

"The police come, every day they say, ’You cannot sell here, you cannot sell here,’" Hamada says, next to his stand in front of a movie theatre.

It took the intervention of a high-profile customer, Mayor Eduardo Paes, to allow him to stay.

His plea to suspicious Brazilians: just get to know us.

That process has already begun in a downtown classroom.

"Today we’re going to speak about the shaddah," says Adel Bakkour, writing the Arabic sign in red marker on a small white board. Ten Brazilian students, most in their late 20s, take notes.

Bakkour says when the war started in Syria, he lost friends and was almost killed. He decided to flee, and Brazil offered him refuge. Within a month of arriving, Bakkour says, he got a Brazilian work permit and free Portuguese lessons.

He wanted to give back‚ so he offered to teach Arabic night classes run out of a Hebrew school. Part of his lesson plan is Syrian culture.

"Some of them ask me if I can marry four women because of the religion," he says, smiling. "Do you really cut the hand of the thief? No, in Syria we don’t."

He says there was so much interest he’s going to start a second class. And his students say their most useful lesson had little to do with the alphabet.

"Last class he was telling us stories about back home. It was interesting hearing what he thinks about Brazil and Rio, how he’s been dealing with everything here," says student Amanda Nicotina.

Bakkour explained "why those people had to flee from home, from their country," adds Catherine Brillant. "This part of the world, I didn’t really know much about it."

Their understanding is coming along slowly. Letter by letter, word by word.

التعليقات (0)