In 2016, with my friend Richard Flanagan, I stopped at a transit station halfway across Serbia. It was a clear day – blue sky from horizon to frozen horizon. Three dirty black buses rolled into the makeshift rest stop and 200 Syrian people climbed down off the big final bus step in need of food and a toilet break. Anywhere else in the world, a group of people like these would be smiling tourists on their way north or south, to the snow or the desert.

Richard and I had followed this river of Syria’s people and all of them were on a journey of escape, fleeing unimaginable horror, men in black clothes, murderous men, murderous war and the end of their homeland. And their destination was thousands of kilometres north in a direction none had ever imagined they would travel, to a future utterly unknown. Among them were doctors and firefighters, teachers, mechanics and university students.

I noticed that day that the young men who huddled their little families around themselves were blank, their eyes full of the shock of profound loss. These men had failed their families; they had run, deserted the homeland that hundreds of their generations had built for so many thousands of years before them. Richard softly ushered these men and their wives to a quiet corner of the complex, with warm coffee and the soothing, loving attitude he shows all his fellows humans, and as they spoke he wrote; they shared stories and they cried.

To quieten the children, I caught their attention. First they were hungry; they ate. Speaking no Arabic, and without translation, I gestured to the little people around me to draw. To tell me about themselves. Grubby little boys drew rainbows and orange trees, and the girls drew princesses and yellow suns. Some lost interest quickly so we used my paper to make aeroplanes with a design my own little boy had discovered, a paper aeroplane that flew and flew, and before long six little boys ran and laughed and watched the plane briefly sweep away the trauma that must surely have travelled with them on those buses, and in their tiny backpacks, all the way from Syria.

One little girl didn’t stop drawing. She barely glanced up at the paper aeroplanes dancing in the blue sky above her. She drew and she drew. She was self-possessed in her determination, and I guessed that maybe I’d been like her when I was six.

She drew an orchard and a garden. She drew fruit trees and the sun, her grandma and her school. She drew flowers and she drew birds. I asked her to draw her home for me. Heba looked into my eyes for a fleeting but intense second, and I saw a seriousness that no six-year-old should understand. Then she drew quickly, deliberately, and at the end passed me the drawing of the end of her home and returned to another drawing of a fruit-laden tree on vivid green grass.

That day Heba made me realise how imperative it is for the world to see her drawing, for the world to see drawings by every child who has survived the Syrian disaster. Big people have big voices and most of them ignore the small voices of the smallest among us. And Heba was one of the most vulnerable little humans I have met, but her voice is big, her story is as graphic as it is tragic, if only we give her a second, to listen and consider the message that she gave me to show you.

Children who have given their art and their voice are living in informal refugee camps in the Bekaa Valley of Lebanon. There are more than a million Syrian refugees in that valley alone. Some gave me their drawings hours after making the terrifying and deadly crossing of the Mediterranean Sea from Turkey to Lesbos and Chios. They have drawn from camps and accommodation in Jordan and Iraq, and some have had their drawings carefully smuggled out of Syria itself. The drawings that are untitled and anonymous were carried from dangerous war zones where parents feared that a simple child’s name would bring evil to their doorstep. Some have lost siblings, some have lost a mum, some lost their dad; every one of them has lost their home. But every child knew that you would eventually see their drawings, and so you would hear their voice, feel their story. There are drawings by children in the suburbs of Sydney, trying to find the meaning of their new lives, and there are others who have drawn from Germany.

I haven’t found Heba yet but I trust she’s safely beginning a new life in Germany.

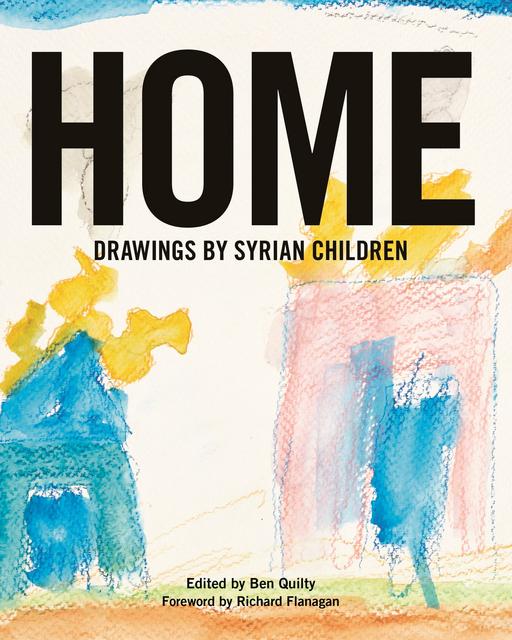

Home – Drawings by Syrian Children is for that little girl, for her future, for the empathy that she deserves from every human on my planet who is luckier than she is. It is a book filled with the truest international language, and it is a language that we big people need to listen to closely and seriously.

This is an edited extract from Home – Drawings by Syrian Children, edited by Ben Quilty, foreword by Richard Flanagan. Proceeds from the book go to World Vision.

التعليقات (0)