"I packed a keepsake for each of my siblings and friends who were killed, to remember them," said Abu Ammar, an opposition activist who had worked on a town council in the rebel-run area. "We went to the graveyard to say goodbye."

He left Daraya by bus in August - when the town was surrendered to Assad after years of regime siege and bombardment - under a deal that gave civilians and fighters safe passage to the rebel-held province of Idlib in northwest Syria.

Syrians have poured into Idlib at an accelerating rate over the last year, forced to abandon their homes in other parts of western Syria that the Assad regime and its foreign military allies have recaptured from rebels.

Sheltering in camps or in the homes of friends and relatives, they are struggling to start over in dire conditions as Idlib becomes ever more crowded with people displaced from Damascus, Homs, and most recently Aleppo.

The latest to arrive are from eastern Aleppo, captured from rebels last month in Assad’s most important gain of the war. Convoys shuttled more than 35,000 people - rebel fighters, their families, and civilians who fear Assad’s rule, out of the city’s last rebel-held pocket. Many of them went to Idlib.

For many, the initial relief of escaping siege was quickly replaced by the realization they may never be able to go home.

Idlib is no safe haven. It remains the focus of fierce air strikes by the Assad and Russian air forces.

"The area has become overcrowded," said Ahmad al-Dbis, a medical aid worker in northern Syria. "It has displaced people from all over Syria, and it’s lacking in services, whether it’s medical, humanitarian, or housing."

Most people displaced from Aleppo spread out across camps and shelters or went to stay with relatives, al-Dbis said.

Starting a new life

"Everybody here is sympathetic to us, because most of them are displaced from other areas," said Hassan Kattan, 25, who was evacuated from Aleppo in December. He left behind a rebel enclave that had been besieged for several months, with large areas reduced to rubble by air strikes and artillery. But finding a new place to live was proving difficult, he said.

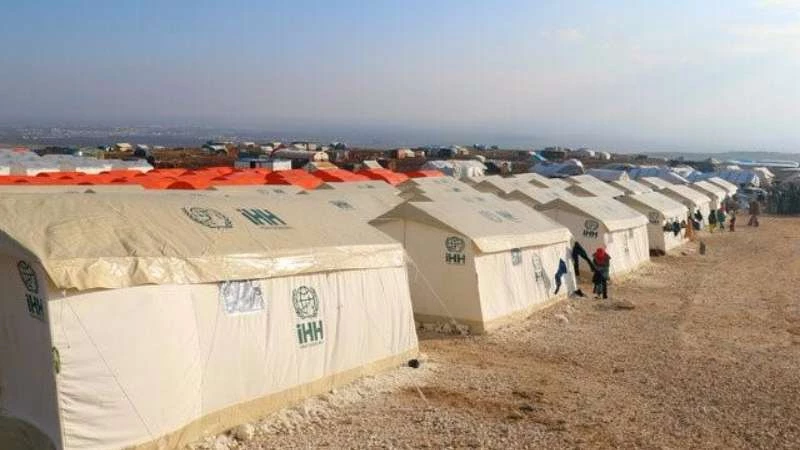

The UN Office for Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) puts Idlib’s population at around two million, including 700,000 internally displaced people. It is bordered to the northwest by Turkey, which has set up a new camp for the displaced in Idlib province.

Although Idlib is a secondary priority to the main population centers of western Syria - Damascus, Aleppo, Homs, Hama and the coast - the Assad regime and its allies will want to recover it sooner or later, raising the prospect of yet further displacement.

Abu Taleb, a medic who came to Idlib with his wife, in-laws, and baby daughter, recalls people weeping on the journey from Daraya.

"I came here, and it’s like I started my life all over again," he told Reuters in an interview from the area, declining to give his full name. "Some people didn’t want to go," he said. "But the siege was suffocating us, and we left out of fear."

Abu Taleb sought refuge in a camp for people uprooted by the war, amid more than 5,000 huts stretched out across the town of Atmeh, planted near the Syrian-Turkish border.

Thousands of tents also cover a hill in the town, near Abu Taleb’s small flat, where he lives with his wife and 5-month-old daughter. "It’s like a village here. It’s better than the tents of course," he said.

"This camp section was empty when we first arrived. We were among the first to come to it," he added. "Now there are people from Aleppo, Hama, Homs, Moadamiya. People came from all over Syria."

Return home seen "impossible"

Local aid groups provide water, bread on a daily basis, and sometimes clothes. But his area still had no electricity. "We use solar-powered batteries. The power runs for about an hour or two a day, so we charge the phones," he said.

Many of the displaced feel stranded in Idlib after leaving their close-knit communities, and they were soon hit by the painful reality that they may never return.

"When you have your own house, your own place to sleep, you have stability in it," said Kattan, who has been staying with a friend since he arrived from Aleppo. He hopes to send his pregnant wife to Turkey for her safety. "But right now, we have to start from scratch", he said.

While some people had managed to open small shops, find work, or rent apartments, many say they are far from settling in.

Tammam Abu al-Kheir, an opposition activist from Darayya who now lives in Idlib, said more people were flooding into the area than aid groups could handle. "Everybody did all they could. The people of Idlib opened up their homes," he added.

Months after arriving from Darayya, Abu Ammar is now trying to find a job. "We still haven’t fully absorbed what happened," he said. Idlib relieved people from the siege, he said, "but it’s still a war zone here."

"Emotionally, we all have hope that we will return home," Abu Ammar added. "But rationally, when I try to think about it, it seems impossible."

التعليقات (0)