While the current butcher of Damascus and his cronies would like Syrians and the world to believe that Syria was insignificant until the coup that put his father Hafez in the presidential seat, this is not the case.

On June 26, 2011, just months after the peaceful revolution began in Syria, Atassi wrote an article he titled: “My Syria, Awake Again After 40 Years”.

In the article, Atassi referred to a 2009 interview of Bashar Assad by National Geographic correspondent Don Belt in which Bashar revealed that he had only entered the presidential office of his father Hafez once at the age of seven prior to becoming Syria’s president by default.

He told Belt how he had run into his father’s office to tell him something and remembered “seeing a big bottle of cologne on a cabinet next to his father’s desk.”

Belt wrote that when Bashar walked into the presidential office for the second time after his father’s death “He was amazed to find it still there 27 years later, practically untouched.”

Atassi went on to describe the untouched bottle of cologne as “an allegory for Syria itself — the Syria that has been out of sight for the 40 years of the Assads’ rule, a country and its aspirations placed on a shelf and forgotten for decades in the name of stability.”

He wrote that another Syria was “appearing before our eyes to remind us that it cannot be forever set aside, that its people did not spend the decades of the Assads’ rule asleep, and that they aspire, like all people, to live with freedom and dignity.”

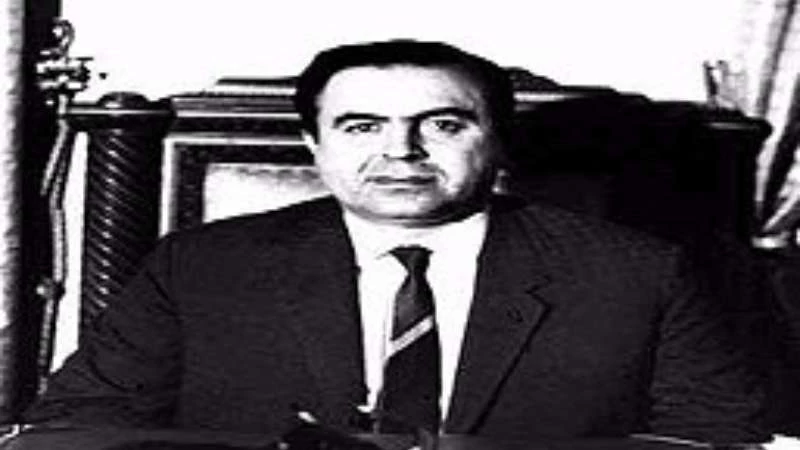

Atassi was only three years old when his father Nureddin al-Atassi was overthrown as president of Syria by a military coup led by Hafez Assad in 1970. Both men were members of the same Baath Party.

He said that at three years of age it took him a while to understand that prison was not only for criminals, but also for prisoners of conscience.

Nureddin al-Atassi spent 22 years in a small cell in Al Mazza prison without ever being charged with committing any crime.

I suppose his crime was perceived by Hafez as holding an office he wanted for himself.

How easy it must have been for the father of Bashar to lock his predecessor away and forget that he had once been Syria’s president and a comrade in the same political party.

Atassi wrote that his family counted their days by the rhythm of their visits to his father. They were graciously allowed one hour every two weeks.

At the end of a struggle with cancer, for which he had been denied medical treatment, Nureddin al-Atassi was finally released. He died in December 1992, merely a week after arriving in Paris on a stretcher.

Atassi went on to say that for “the great majority of Syrians, the forgotten Syria meant a police state, a country governed with an iron fist. It meant a concerted international effort to keep a dictatorial regime in power in the name of regional stability — preserving the security of Israel and maintaining a cold peace on the Golan Heights, like the snow that covers Mount Hermon.

“The forgotten Syria meant thousands of political prisoners packed for decades inside the darkness of prisons and detention centers.

“It meant disappearances that left families without even a death certificate.

“It meant the tears of mothers and wives waiting since the 1980s for their sons and husbands to return, even if wrapped in a shroud.

“It meant daily humiliation, absolute silence and the ubiquity of fear.

“It meant networks of corruption and nepotism, a decaying bureaucracy and a security apparatus operating without control or accountability.

“It meant the marginalization of politics, the taming of the judiciary, the suffocation of civil society and the crushing of any opposition.”

History continued to move forward in the rest of world.

“But the regime buried its head in the sand,” wrote Atassi, “living the delusion that it could keep history out — if only it abused its people enough.”

When Hafez Assad died in 2000, the regime attempted to defeat the certainty of death by transferring his power through inheritance to his son.

Hopeful that the son would rule differently as a result of his western education, Syrians called for their new president to turn the page and proceed toward democracy.

Instead he continued to play by his father’s rules and had the most prominent activists arrested and thrown in prison.

Through four decades the Assad regime refused to introduce any serious political reform.

But the Syrian people continued to move forward. The population grew exponentially and eventually more than half of all Syrians were under the age of 20.

With widespread unemployment and the wealth of the nation held tightly in the hands of a small class of regime members and their cronies, something was bound to happen that would get history moving forward again in Syria..

Many western observers doubted whether the Syrian people had it in them to revolt, but they underestimated the depth of their dissent and the strength of their determination.

“It was no surprise that at the moment of truth, Syrians opened their hearts and minds to the winds of the Arab Spring,” wrote Atassi.

Nureddin al-Atassi had governed Syria for four years, but unlike Bashar, his son inherited neither power nor fortune.

“What I inherited was a small suitcase, sent to us from the prison after he died. It held literally all of his belongings after 22 years in confinement. All I remember from this suitcase today is the smell of the prison’s humidity that his clothes exuded when I opened it,” Atassi wrote.

In 2011 he vowed that the next time he visited his father’s grave he would tell him that the big bottle of cologne had been broken and the scent of freedom was once again spreading across Syria.

التعليقات (0)